Seeds of Survival Take Root at Smith

Smith Quarterly

The botanic garden nurtures a powerful connection to Hiroshima, Japan

Illustration by Ping Zhu

Published February 17, 2025

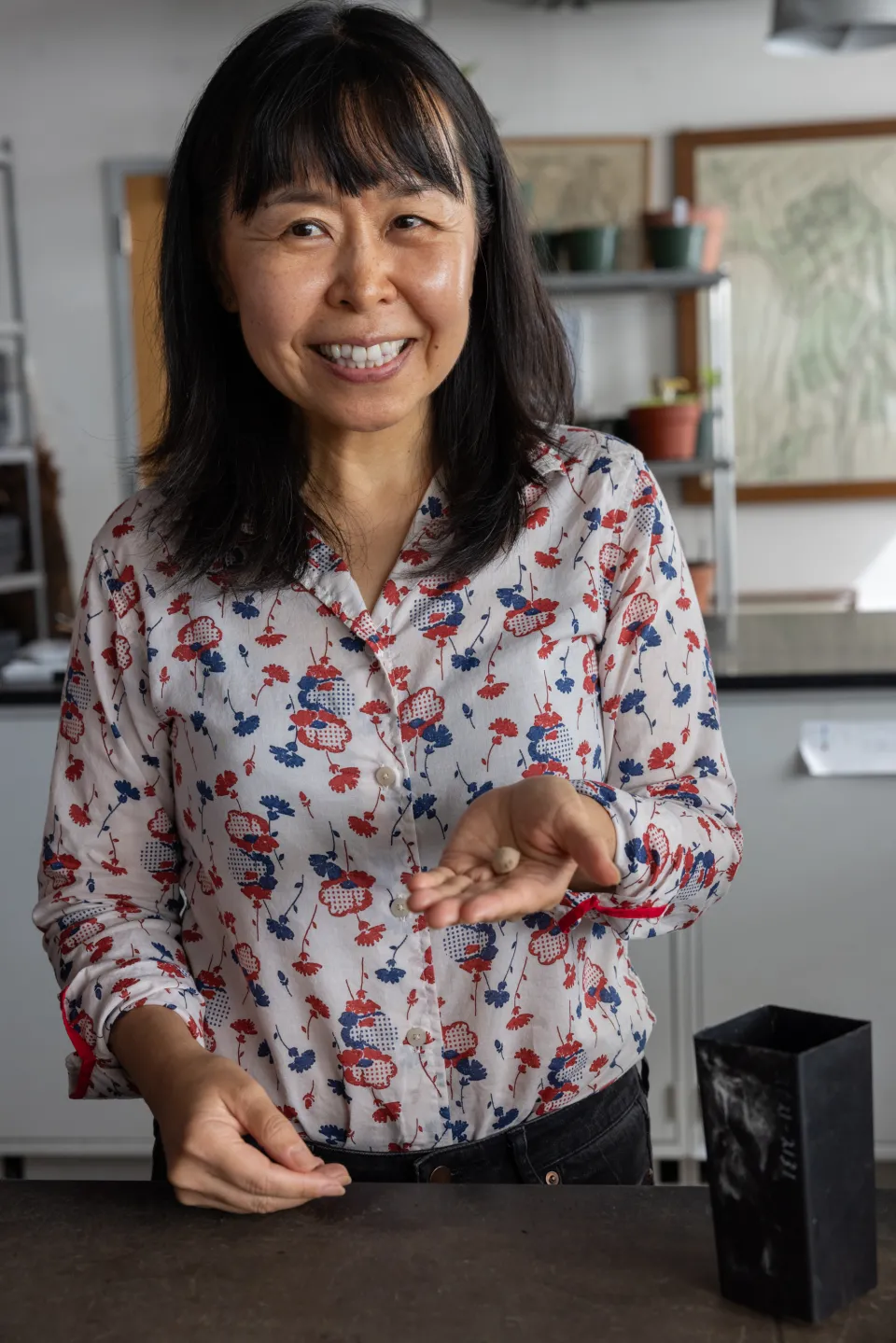

As Professor Atsuko Takahashi holds the small seeds carefully, she realizes her hands are shaking.

“Hello, babies,” she whispers.

The seeds—all seven of them—are from a ginkgo tree. They are small and tan-colored, like unopened pistachios. The species they represent is not particularly rare or exotic. But they are incredibly special seeds: the progeny of a tree in Hiroshima, Japan, that survived the devastating impact of an atomic bomb in 1945.

Today, Takahashi, a senior lecturer in Japanese at Smith, and a few of her students and staff from The Botanic Garden of Smith College are working with the Japanese nonprofit Green Legacy Hiroshima (GLH) to create a new story for the seeds. The group hopes the seeds will sprout into a grove of trees—a place that can serve as a reminder of the legacy of war and its aftermath, but also of reflection and peace.

Photographs by Jessica Scranton

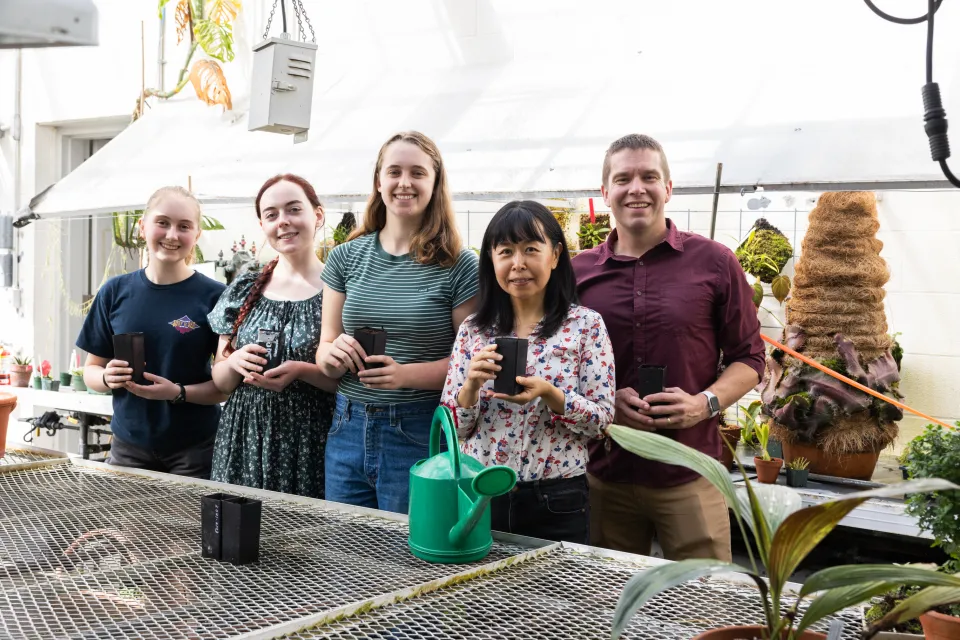

On a recent Friday, botanic garden director John Berryhill, Takahashi, and three of her students—Astrid Johnson ’26, Claire Edmonds ’25, and Sian Bareket ’25—gather in a classroom at Lyman Plant House to pot the seven seeds and talk about what they hope will come from the plantings.

“Oftentimes with historical tragedies, people still associate different names of cities with only the destruction,” says Bareket, who studied abroad in Japan and was surprised to discover during her travels that Hiroshima is now a bustling city. “I think it’s important to highlight both the story and the life that comes after.”

Botanic garden staff plan to tend to the GLH ginkgos in Lyman for the next five years in the hope of growing them into trees that can be planted in a grove near Paradise Pond. As the saplings mature, Takahashi and her students will regularly update a website they created for the project to further engage and educate the community.

More than other cultivation efforts, Berryhill says the partnership with GLH is intended to be fully multidimensional, engaging a range of departments and inspiring “more of a mission-focused project than a simple horticultural task.”

“This isn’t an exotic specimen,” Berryhill says. “This is a story about human resilience, human suffering, violence, and peace. That story is what we’re curating. And capturing the power of plants to tell that story is something we want to do as a botanic garden.”

The mission is a personal one for Takahashi, who is from Shizuoka, Japan. She can recall growing up in a country where stories about the impacts of World War II were embedded in her earliest elementary school classes. It was there that she learned how in August 1945 the United States detonated two atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing between 150,000 and 246,000 people.

“In Japan, everything is kind of touched by the story of the bombing,” Takahashi says. “We read picture books about the experiences and literature appropriate for young readers. In that way, everybody knows what happened.”

When she was a fifth grader, her family went on a trip to the south of Japan and made an unexpected detour to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum—places that document the aftermath of the bomb. For a young Takahashi, the experience was heartbreaking.

“The memory was really traumatic,” she says. “It was a very powerful experience for me. I was old enough to understand, but I didn’t have the tools to share the feeling with my parents or anyone.”

Decades later, Ruby Shea ’24—a student from Takahashi’s fourth-year Japanese class—returned to the area during a semester abroad in Japan and learned something that Takahashi had not: Certain trees survived the impact zone. Hollies, crepe myrtles, weeping willows, camphor trees, and Japanese persimmons that had been blasted and burned had resprouted.

Shea also learned that, in 2011, GLH was founded to safeguard these A-bomb plant survivors and propagate their seeds with help from partners around the world. The hope was that as the seeds grew, they could serve as tiny green ambassadors, spreading a message of peace and disarmament. Shea looped in her friend Kuni Anderson ’24, who was also abroad in Japan, and together they approached Takahashi and Berryhill about having Smith apply to be a GLH partner.

In August 2024, after a yearlong application process—during which Shea and Anderson graduated, handing the student side of the project off to Johnson—a small brown envelope arrived at Lyman.

The seeds GLH chose for Smith were from a ginkgo biloba that had been growing at Shukkeien Garden, which was created by the famed samurai Ueda Soko in 1620 and is located just 1,370 meters—less than a mile—from the epicenter of the atomic blast. The organization notes, “There are three A-bombed trees in the garden: a ginkgo, a black pine, and a muku. The ginkgo tree is more than 200 years old. It is slanting toward the hypocenter because after the blast moved outward from the city center, the air gushed back in.”

For Takahashi, the entire project has made her rethink her experience in Hiroshima. She has long believed she would never return to the site that so deeply affected her as a child, but says her students have been inspiring. Working with them on the seed project, she says, has given her a sense of catharsis. For the first time, Takahashi has started to think about taking her own children to visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum one day. And she’s already begun to talk to them about what happened: the war, the terrible bomb, and the mother tree that survived it all. “I feel like it’s a step,” she says.

“Something new is starting. That’s how I felt, to be honest,” Takahashi says. “When I had a seed in my hand … I felt like I was carrying a baby.”