The Longest Night

Alum News

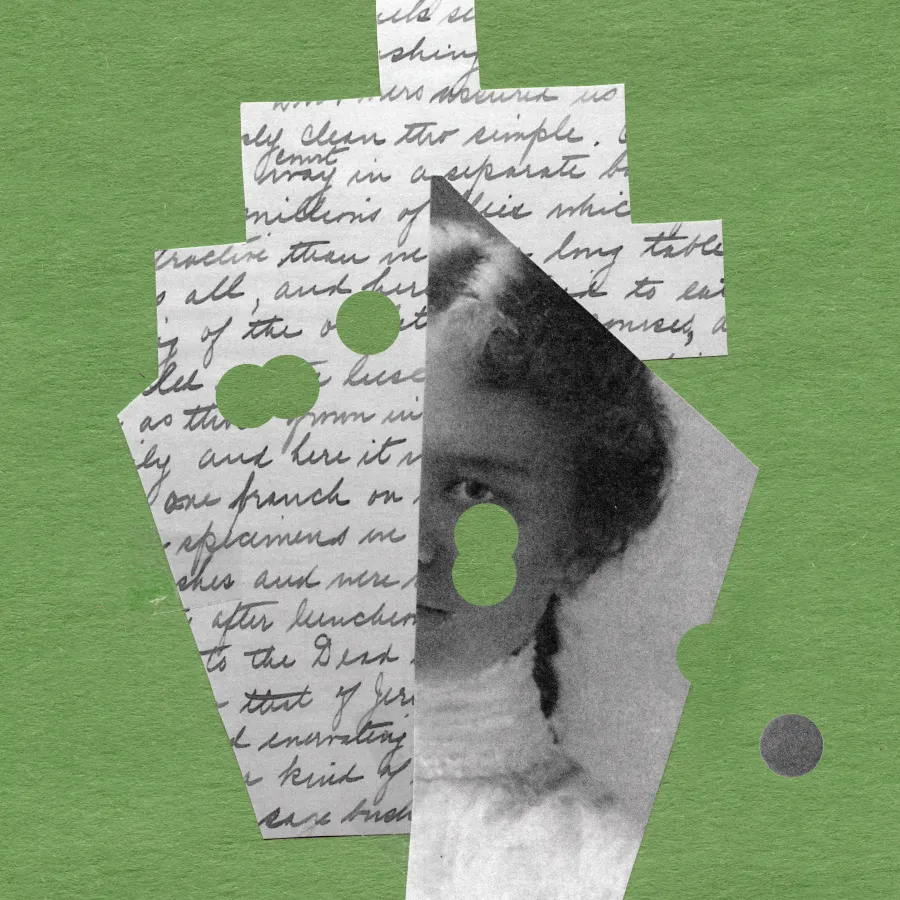

Madeleine Newell 1903 survived the Titanic sinking—and never spoke about it. Her great-niece Sandy Madeleine Sweeney Gallo ’79 tells her tale.

Illustration by Najeebah Al-Ghadban

Published July 17, 2024

Arthur Newell had a wonderful surprise in April 1912 for his daughter Madeleine Newell 1903 and her sister Marjorie. They were in Paris at the end of a three-month tour through the Middle East and France. The good news? He had booked first-class passage home on the marvel of the ages—the RMS Titanic, the world’s largest steamship.

Photograph courtesy of Mary Payne.

Sandra (Sandy) Madeleine Sweeney Gallo ’79 knows all about Madeleine and Marjorie.

She is a trustee and the convention coordinator of the Titanic International Society, an association whose members are devotees of all things Titanic and other maritime disasters. Her great-aunt Madeleine, for whom she is named, survived the sinking, as did her grandmother Marjorie. As a child, Gallo knew her family’s matriarchs had been aboard the doomed ocean liner, but its voyage and last terrible night were never discussed. Madeleine is the only known Smithie to have been a survivor of the Titanic’s sinking in the North Atlantic on April 15. Now, 112 years later, Gallo is sharing details of her great-aunt’s life, her fateful trip, and its aftermath.

Arthur’s wife, Mary, had not felt up to making the three-month European trip. She stayed home in Lexington, Massachusetts, with the family’s middle daughter, Alice.

Hours after the sinking, the steamship Carpathia picked up the sisters. Madeleine sent her mother a telegram via the ship’s wireless telling her that she and her sister were safe. Having received no word about Arthur, Mary sped to New York and waited at the Hotel Manhattan, praying that all three would arrive unharmed.

Heavy fog and ice delayed the Carpathia’s arrival until the evening of April 18. Thirty-thousand people crowded the pier, hoping to meet survivors. “They were pictures of woe,” according to a family friend, George Milne, who met Madeleine and Marjorie there and whisked them away from the reporters. After making their way through the mob, the sisters raced to the hotel, possibly still wearing the clothes they had on at dinner the night of the sinking.

When Mary saw them get off the elevator alone, she screamed. By this time, the search for survivors had ended. Her husband of 34 years was dead. In the years to come, she frowned on any conversation about the tragedy.

The Newell sisters. From left, Alice, Madeleine, and Marjorie.

Photograph courtesy of Mary Payne.

“She was a very frail little woman. She mourned for the rest of her life,” says Gallo, a global accounts manager at HelmsBriscoe, a hotel site selection company for meeting planners.

At Smith, Madeleine, the eldest daughter, delighted in studying the Bible and Latin, Greek, and German. Her passion for antiquities flourished during her family’s travels abroad. In a diary, she recorded her adventures by drawing detailed pictures of pharaonic tombs and describing their mysteries. She recounted what it was like to be in a “cramped position” on a donkey, which meant riding sidesaddle while wearing a corset, a long dress, and high lace-up boots.

She adored her father. A self-made man, he started as a bank clerk and rose to become president of the Fourth National Bank of Boston. Now—in that early spring of 1912—he told his daughters to pack their bags for the hourslong train trip to the quay in Cherbourg, France, where the Titanic where the Titanic awaited its passengers.

The 883-foot-long liner paused in the French harbor long enough for smaller vessels to ferry passengers. On their way out, the Newells marveled at the ship’s sleek black hull. They gaped at the four stylishly swept-back funnels that towered over its superstructure.

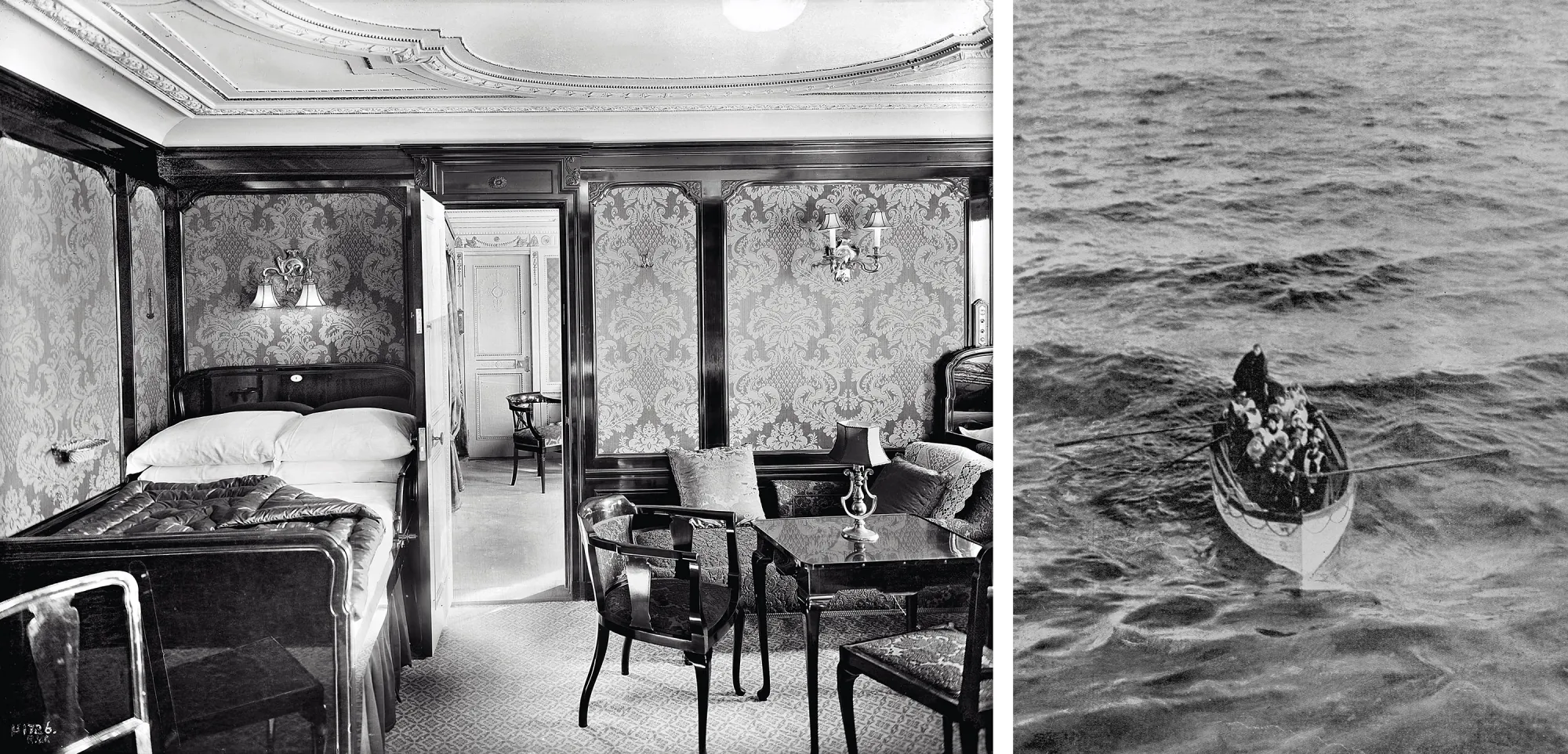

The Newells’ two staterooms, while hardly as luxurious as the suite of millionaire John Jacob Astor, each cost $18,300 in today’s money. During the voyage west, Madeleine and Marjorie enjoyed the sunshine while lounging on deck chairs. They explored the ship’s impressive library and perhaps gave impromptu violin recitals. The Newell daughters took music seriously. Every Sunday after church, they gathered in their parlor and performed with their father and mother accompanying them on cello and piano, respectively.

Marjorie, left, and Madeleine at home in Massachusetts.

Photograph courtesy of Mary Payne.

After retiring to their stateroom to practice their violins, the sisters went to bed—only to be roused by a jarring sensation. “The shock was not sudden, but was more like an earthquake.”

After four days at sea, on Sunday, April 14, Madeleine, then 31, and Marjorie, 23, went to dinner, the event that marked the social climax of the voyage. They made their appearance in long gowns with trains. It was the first time young Marjorie had ever worn one with such a sweeping overskirt, and the sisters eyed the even more opulent attire of the society ladies.

But in a reception lounge that evening, they met a woman who was in anything but a festive mood. “I wish we weren’t going so fast,” she told them.

The Newells’ last meal was exquisite. Its highlights included decadent filets mignons Lili topped with foie gras and truffles and served in a buttery wine sauce; Punch Romaine, a rum-spiked palate cleanser of shaved ice served between courses; and a scrumptious baked Waldorf pudding.

Madeleine and Marjorie ate until they could eat no more. Their usually serious father kidded them, asking, “Do you think you can hold out until morning?” knowing they would certainly not be hungry before breakfast.

After retiring to their stateroom to practice their violins, the sisters went to bed—only to be roused by a jarring sensation at 11:40 p.m. As the New York City newspaper The Evening Post reported in an account published on April 19, 1912, “The shock was not sudden, but was more like an earthquake.”

Soon, their father appeared. He told them to put on their warmest clothes and life vests. Arriving on deck, they and other passengers were calm, even though the liner sat dead in the water. They could feel it listing to starboard. Madeleine showed no fear, even though to her it looked as if the Titanic had hit an iceberg nearly head-on.

“I had perfect confidence in the great new ship, and the crew assured us that there was no danger,” she recalled.

As sailors lowered Lifeboat 6 to deck level, one of the ship’s great funnels erupted suddenly above them. Its explosive release of steam surely terrified everyone, including Madeleine. Second Officer Charles Lightoller called for women and children to come forward. Arthur carefully helped his daughters into the lifeboat alongside an American socialite, Margaret Brown—who would come to be known as the “Unsinkable Molly Brown.”

The last thing he said to them, according to Marjorie, was, “It seems more dangerous for you to get in that boat than to remain here with me.”

Madeleine recalled their parting differently, according to an account given by one of her friends years later. “Come along, too. There’s plenty of room,” the daughters implored. “No,” their calm father replied. “I’ll come later.”

Orders were orders. The gentleman did as he had been told. His favorite saying was, “I love to make things right.”

“Many ... refused to leave the big ship, and the men ... stood back and let the women get into the boats first,” Madeleine recalled. “They were the most chivalrous men in the world.”

Two men and several women, including Marjorie, rowed the boat about a mile from the ship, fearing that if it went down its suction would doom them. “The sea was perfectly calm, as smooth as the palm of your hand,” Madeleine remembered. The end came at 2:20 a.m., less than three hours after the collision. Madeleine gave a detailed account. “The Titanic began to sink faster. The water got into the engine room against the boilers, I think, for we heard a terrific explosion,” she said. “The stern of the Titanic lifted way out of the water, and the ship’s keel showed. The tipping of the vessel threw everything toward the bow, and the ship went to the bottom.”

Left: A first-class stateroom on the Titanic. Right: Survivors in one of the Titanic’s few lifeboats (right).

CalimaX/Alamy stock photo (left) and Chronicle/Alamy stock photo (right).

Other than the newspaper interview Madeleine gave after disembarking from the Carpathia, she never spoke about the tragedy for the rest of her life. She occupied herself doing volunteer work for nursing homes for elderly women.

She never married. For the next 45 years, she and her sister Alice cared for their mother, who died in 1957 at age 103. Madeleine lived to be 89 and passed away in 1969.

“She could have been destined to go on and, who knows, be a professor or a social worker, but her life changed,” Gallo says. “Now she became the head of the family. Her job was to take care of her mother.”

“One of [Madeleine’s] strongest characteristics was her desire to learn,” says Gallo's sister, Mary. “It was almost like she was desperate to learn as much as she could as fast as she could. Her father never went to college. He wanted to give her that chance to grow and learn as much as she wanted. He wanted the best for her where she would thrive.”

When Madeleine fled her stateroom, she had the presence of mind to take her diary. She wrote nothing of her shipboard days on the Titanic. Its last entry reads, “April 10. Left Paris for Cherbourg about nine o’clock.”

Marjorie had turned down an opportunity to attend Smith. (Her daughter Rosalind Robb Livermore was a member of the class of 1940.) She chose instead to pursue her interest in music, a passion that led her to co-found the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. She was the Titanic’s last surviving first-class passenger, dying at age 103 in 1992. Out of respect for her mother and her sisters, she waited until long after they passed away before beginning to speak publicly about the disaster, in her 90s. (Many details in this article come from her accounts.)

Gallo's lifelong fascination with the Titanic first revealed itself in seventh grade. She wrote a short story about its sinking from the point of view of her great-grandfather’s onyx and rose gold ring. When his body was recovered, rescuers found the heirloom on his hand. The family dubbed it the “Neptune ring” because it features a trident and a likeness of the Roman god. Gallo's sister, Mary Payne, has the ring in her possession and wears it every year on the anniversary of the sinking.

“I’ve worn it sometimes,” says Gallo, who lives in Wilton, New Hampshire. “I want to honor my great-grandfather. He was a very stalwart Christian man. I think about how he lived his life. I know that he stood on deck helping people in need. That’s what Marjorie said he would have done.”

Madeleine’s silence about the sinking extended to her relations with Smith. When asked in 1956 if she would like to submit a class note detailing her experience, she replied, “I am rather reluctant to have anything of the kind printed in the Quarterly.”

Freelance writer George Spencer is a former executive editor of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. He profiled former Disney CFO Christine McCarthy ’77 for the Fall 2022 issue of the Smith Quarterly.

The Titanic's Enduring Legacy

By George Spencer

When Sandy Madeleine Sweeney Gallo ’79 was a child, neither her great-aunt Madeleine nor her grandmother Marjorie talked about the disaster. “Madeleine’s memory was just of the ship going down and everybody screaming,” she recalls. Here’s what the French and history major says about being a descendant of Titanic survivors.