Jess Gersony Intersects Art and Social Justice with Plant Physiology

Faculty

Jess Gersony

Published January 22, 2024

When is a STEM class more than a STEM class? When it’s being taught by Jess Gersony, assistant professor of biological sciences. In the two years that she has been teaching at Smith, the plant physiologist has brought her full self to the classroom, weaving elements of her experiences as both a professional tap dancer (she has been in several dance companies) and poet (her collection I Could Collect a Lake was published last year) into lessons on how plants work and the consequences of climate change. The result is a novel approach to teaching that embraces interdisciplinary coursework and engages students in the full breadth of the liberal arts.

“I got into the field because I care about climate change,” says Gersony, “but I wanted to bring my whole self into teaching—my artistic side and my social justice side, as well as my plant biology side.” And that is exactly what she has managed to do during her time at Smith.

Marge Poma Alarcon ’23, a research technician in Gersony’s lab, says Gersony’s approach is unique, especially in the sciences. “It makes sense to connect the arts and social justice with climate change and plant physiology because an intersection already exists,” Alarcon says “It has enabled me to understand the concepts I learned in the classroom as they apply to real-world situations.”

The Artful Side of Botany

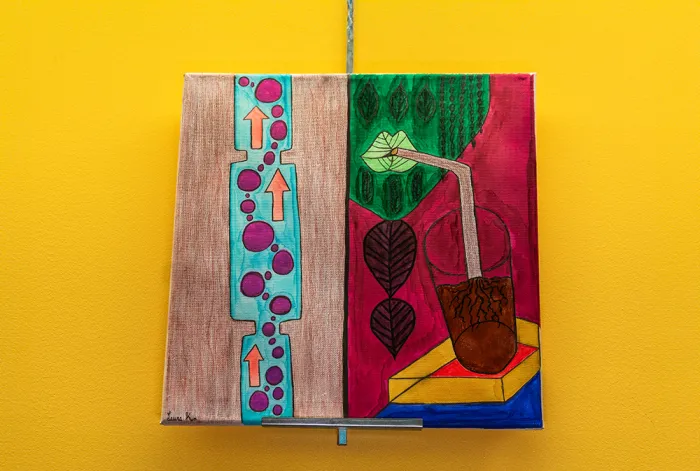

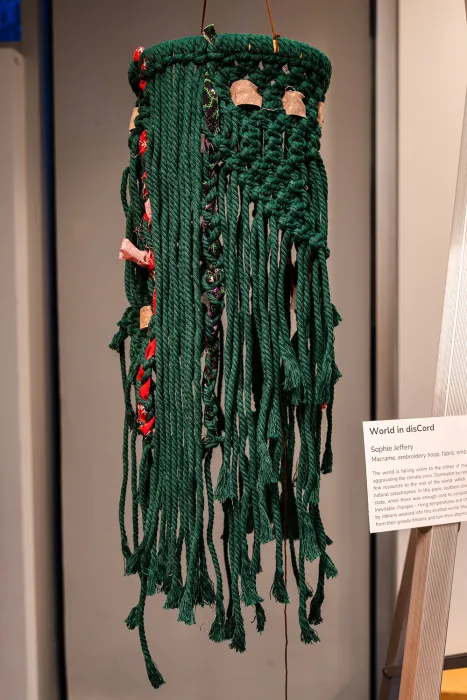

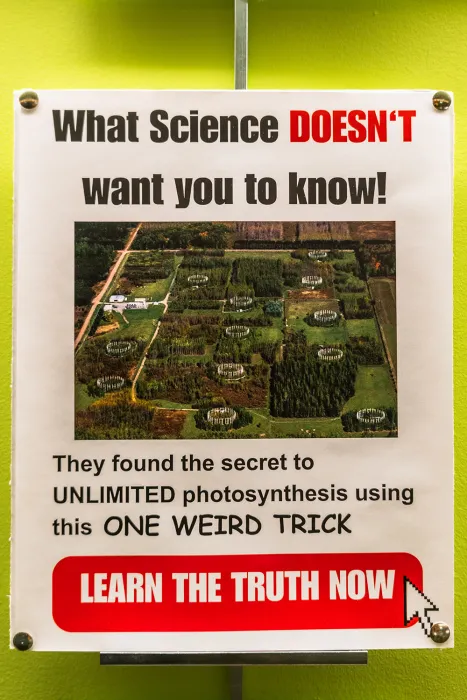

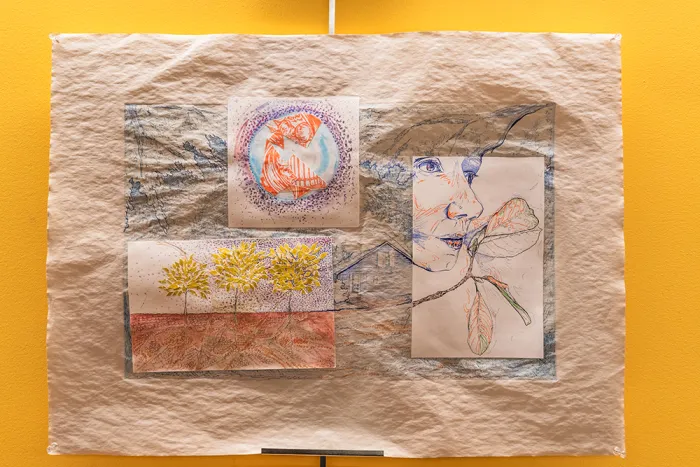

Gersony’s seminar, Understanding Climate Change through Plant Biology and the Arts, is a perfect example of her teaching method in action. Students are required to complete three art projects related to course material, which covers a range of topics, from the movement of shrubs into the arctic tundra because of warmer temperatures (shrubification) to the mortality of trees due to increased drought. Once their projects are complete, students then show their pieces in class, without any verbal or written explanation of what the project is or what it illustrates. Gersony frames the class discussion around three questions: What are you looking at? How does it relate to the course material? How does it make you feel? Following the discussion, the artist is then invited to talk about the work and their process. Importantly, only positive comments from others are allowed. “Students make amazing art in class and they inspire each other. This process builds community in the classroom, enabling the students to feel comfortable and learn more,” Gersony says. “It allows the students to bring their whole selves into a STEM classroom and really get to know one another.”

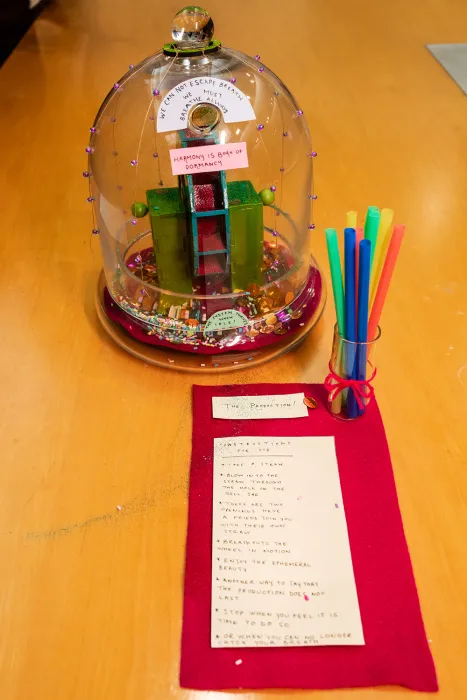

In December 2023, an exhibit of the class’s art projects allowed others on campus to see Gersony’s students’ creations, which included poetry, paintings, collages, sound recordings, fiber arts, and handmade books. For the show, students provided labeled descriptions of their work. An interactive sculpture by Chlo Gold ’25, titled The Production!, illustrated the process of carbon dioxide (CO2) fertilization. Using a bell jar, straws, sequins, and beads, participants were encouraged to blow through a straw and observe as the wheel inside the bell jar started moving, with breath as the catalyst. “As we learned in class, CO2 fertilization, which increases CO2 in the atmosphere, is purported by climate change deniers to benefit plants,” says Gold. “However, the positive effect is short lived and eventually these heightened CO2 rates deplete the system and prove detrimental to plants. Rather than demanding productivity and output from plants, my piece poses an alternate reality where we embrace slowness and smallness from our botanical kin, and for ourselves.”

Despite an interest in botany, Gold struggled in traditional STEM classes and says being in a Gersony’s class has been life changing. “Art is how I make sense of the world, and it’s such a relief that I can bring the maker in me to plant physiology courses,” Gold says. “Science is moving in a new direction, allowing us to bring all of ourselves to the field, and that shift is vital.”

A Unique Opportunity

For Gersony, that new direction for science also includes social equity. When she heard about the Urban Forest Equity project in Holyoke, Massachusetts, she saw a perfect opportunity for her students to sharpen their research skills while contributing to a local community project seeking to combat climate change.

Led by Yoni Glogower, director of the Holyoke Office of Conservation and Sustainability, the Urban Forest Equity project is an effort to improve the environmental and equitable state of the urban forest of the city of Holyoke, including cultivating existing trees and creating educational outreach about the city’s trees. Holyoke, which is about 22 square miles and has a population of more than 38,000 residents, received $120,000 in grant funding from Greening the Gateway Cities Program, in addition to other grants, to plant a variety of types of trees in spaces around the city where there was little tree canopy and lots of water-resistant surfaces. The benefits of tree covering in urban areas are well documented. Trees provide effective stormwater management, cooling for the environment, and are associated with better mental health, higher rates of recreation, and lower rates of obesity among residents.

Gersony reached out to Glogower to inquire if she and her students could support the Urban Forest Equity project. She also contacted Sage Franetovich, professor of biology at Holyoke Community College (HCC), who was very eager to have Gersony’s students participate. Initially, Smith and HCC students were brought to Holyoke to inventory existing trees. They provided support to the city in moving forward with the makeup of their urban forest, and students learned about tree identification and urban tree methods. After that, HCC and Smith students took to the streets of Holyoke with clipboards and measuring tapes in hand to implement the larger-scale, long-term research project of measuring and recording the diameter of the trees planted as part of the Urban Forest Equity Plan. The data will serve as a baseline, with measurements taken each year (for an indefinite period) to track the trees’ growth.

Photo: Holyoke Urban Tree Project

MJ Kabongo ’23 measures the diameter of an older tree in downtown Holyoke, last summer, as part of the Smith College/Holyoke Community College Urban Tree Project research study.

“There is a lot of information that you can gain through these measurements,” says Gersony. For instance, by knowing a tree’s diameter, you can calculate the number of leaves a tree has or the amount of carbon underground in the form of roots. In a few years, researchers will start to get a sense of which trees are thriving and which are struggling, and will inform the city as to which species to plant in the future. For trees not growing as well as they should, steps can be taken to adjust their care.

“The Urban Tree Project in Holyoke is a fantastic initiative,” says Gold, who was one of the students measuring the trees. “It’s incredible to me that this work will span time, and have such a meaningful effect on the ground.”

Isabel Thompson ’24, who also participated, echoed the idea that the results of the project will have long-lasting benefits to the community. “My key takeaway was the importance of working directly and laterally with community stakeholders to design investigations that are useful beyond dominant academia, especially by marginalized people,” Thompson says.

Building community through STEM

Gersony’s teaching style has garnered accolades from current and former students, like Poma Alarcon, who says, “Jess Gersony makes room for every student to voice their thoughts on readings and assignments, fosters community-building through art and research, and sparks curiosity when unraveling the unique ways technology in plant physiology is developing.”

Photos by Jess Gwilliam