‘I Am Not Black or a Woman. I’m a Black Woman’

Alum News

Published March 13, 2019

“What defines you more—your gender or your race?”

The question came floating toward me like a slow-pitch softball, tossed by a white friend, surrounded by other white friends of mine as we lounged in Albright House, where, as a first-year, I had been the only black resident, struggling to find my fit at my unfamiliar, mostly white all-women’s college. Now a senior, I finally felt at home. Their question, though, threw me.

It came during a vaguely philosophical conversation, the kind usually launched over late-night pizza when everyone’s avoiding their studies and sleep. I had long since fielded inquiries about why I ironed my clothes, lotioned my skin, oiled my hair and had mostly black art on my walls, but those were small, meaningless curiosities by comparison.

This one cut to the heart of who I was, whose I was and how I saw myself. I had never been asked such a thing. Never even considered it. Unnerved, I understood that it came from the same well-intentioned and stunningly insensitive place as the always jarring, “I don’t really see you as black.” It was rooted in their struggle to define and embrace me, which had nothing to do with my own.

Whether the question was really about allegiances, defining physical characteristics or the forces that most shaped my experiences, perceptions and politics, wasn’t the answer obvious?

The fact that they weren’t asking this of each other said it all. “At Smith,” I said, “my race defines me more.” Surely there was more to say, an awkward but important conversation to be had. But not then. I was grateful that we moved on.

I have come to understand in the years since that my truest answer is this: I can’t choose. I am not black or a woman. I’m a black woman. One whole being, not the sum of separable parts. My experience in the world is unique to black women—distinct from any man or any woman of any other race, particularly the white race, whose advantages are still too often reinforced and lever- aged at the expense of my community, my children, myself. My race is systematically oppressed in this country, as ismy gender, so the intersectionality of my experience as a black woman is darkly clear. A strange mix of acceptance and resistance—both survival tools—shapes me in every way.

That night in Albright has come back to me repeatedly in recent years as I’ve watched white women align themselves with those who consistently derail my interests, their interests as women and the interests of their own white sisters. At the black-owned company where I work, I lead a brand created to celebrate, connect and encourage women of color to seek and leverage power—not only for themselves, but for each other and for all.

White women have not proven to be our natural allies, which again raises that question once posed to me. I wish I’d thought (or had the courage) to return it back at Smith. It would have opened a dialogue that is desperately needed if we’re to collectively grow, prosper and leverage power as women, together.

Smith should be leading such conversations, especially now, when the question hovers around us, weighty and unspoken, its answer more critical than ever. What do white women stand for? Who do they most want to stand with them? What defines them more, their gender or their race?

Writer and journalist Caroline Clarke ’85 is the chief brand officer for Women of Power at Black Enterprise magazine.

This story appears in the Spring 2019 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

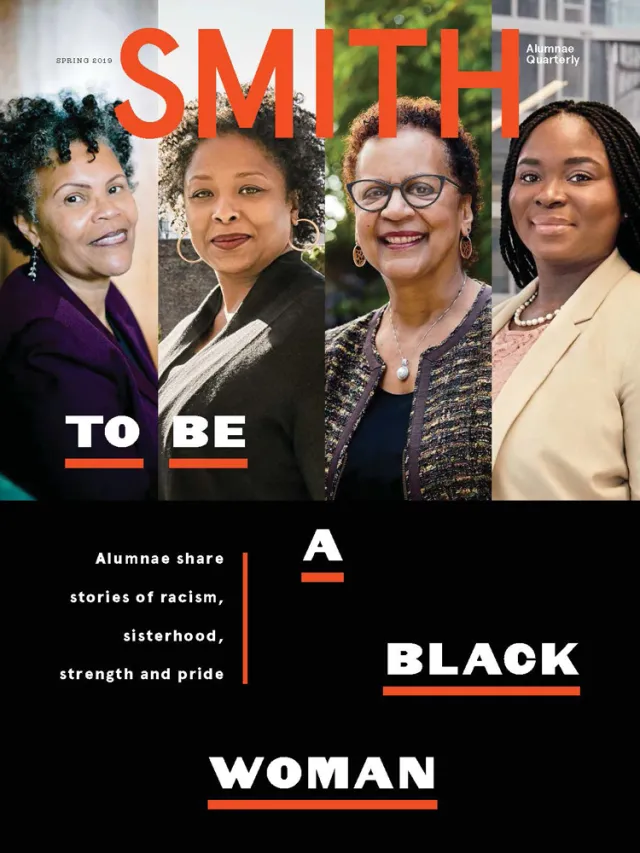

To Be a Black Woman: Alumnae Share Stories of Racism, Sisterhood, Strength and Pride

Deborah Archer ’93, “I’ve Picked a Lane. It’s Racial Justice.”

Billy Dean Thomas ’14, “I Felt Like I Was Being Tokenized”

Charlise Lyles ’81, “Who Came To Soothe My Soul? All My Black Sisters.”

Lori Tharps ’94, “I Yearned for a Comfort and Confidence in My Blackness”

April Simpson ’06, “If we listen to how others define us, we remain stuck” Q&A with Sandra Williams ’75, senior vice president at CBS Television

Deanna Dixon ’88, “I’m Proud That Our Students Hold Us Accountable”

Joyce Young ’75, “Challenging the Status Quo by Writing My Truth”

“What Excites You, Gives You Joy, Gives You Hope About Black Women in the World Right Now?

Sabine Jean ’11, “Am I the Only Black Person in Here?”

Vickie Shannon ’79, “Racism Is Their Problem—Not Yours”

Stephanie Mickle ’94, “Black Women Can Rally Voters, Influence Elections and Win”