Girl on a Train

Alum News

A little-known, recently rediscovered short story by Sylvia Plath ’55, written during her sophomore year at Smith, laid the groundwork for some of her most influential works—and may have foreshadowed the author’s own fate.

Published March 17, 2021

In May 2016 I bought the short story “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom” by poet and author Sylvia Plath ’55, the original version of which had been written in the fall of 1952 when she was a 20-year-old undergraduate in the English honors program at Smith.

The uncorrected draft with a grade of A-, now held by the Lilly Library at Indiana University, had been written for English professor Robert Gorham Davis’ course Studies in Style and Form. Plath later decided to revise the story and submit it for publication, but it had been rejected. It was that version—the unpublished typescript—that I bought as one of four unsold lots at a London auction in 2016; my son, an art dealer, had negotiated the post-sale of this lot. When the story arrived at my home in New York and I read it in its entirety, I realized that I now owned the final copy of a compelling tale written by Plath—one that unites many issues of Plath’s life and writing, including her suicide as explored in the story’s allusions to Dante’s Inferno. Thus began the saga of a manuscript that had languished undiscovered for several decades.

Over a year later at a symposium I chaired in October 2017, Paula Deitz Morgan ’59, editor of The Hudson Review, expressed interest in the story for possible publication in her journal. She also brought it to the attention of Plath’s publisher of record, Faber & Faber, who asked me to fax scans of the manuscript to its editors. Faber published a handsome hardcover edition as part of its 90th-anniversary story series in January 2019, and the American rights were assigned to HarperCollins, which published paperback and hardcover editions. The story was also reprinted by The Hudson Review in the spring of 2019. Since its publication, Plath’s story has been translated into six different languages—Catalan, Dutch, French, German, Portuguese and Spanish. In December 2019, a staged reading presented by undergraduates in the Smith College theatre department, under the aegis of the college’s Poetry Center, demonstrated its dramatic potential.

“The unselfconscious revelations of [Plath’s] innermost thoughts contained in her journals fascinated me and fostered my determination to collect her reminiscences in poetry and prose.”

For me, the acquisition of “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom” represented the latest find in my three-decades-long journey as a collector of Plath’s work. I first met Sylvia when we were both students at Smith. She was that rarity on campus—a published poet. I knew her not only by reputation but also as an acquaintance, since we were both English literature majors, and I admired her work ethic. My main encounter with Sylvia occurred in April 1953, when we competed for a summer guest editor position at Mademoiselle magazine. That morning, the two of us met during chapel with Marybeth Little, college board editor of the magazine, who was attending an Arts and Morals conference at the college. To her brother, Warren, Sylvia wrote, “Whoop-de-do, I am going to cover this conference for the Hampshire Gazette.” Writing to her mother, she expressed concern about competing for the Mademoiselle guest editorship with “20 top girls” who are “tremendous in art, gov [and] fashion.” To no one’s surprise, however, in mid-May, Sylvia was named guest editor representing Smith; I was one of 10 runners-up appointed to the magazine’s college board.

It wasn’t until much later, after I had read Sylvia’s published journals, that I learned of how the death of her father, which left her mother as the family’s sole breadwinner, fueled her anxiety about money and drove her quest for scholarships, fellowships, academic prizes and summer jobs to support her education and provide living expenses. I could also identify with the problems she faced in balancing marriage and motherhood with her professional ambitions—a tension that women from our generation knew all too well. And I continue to find poignant the story of her marital separation from Ted Hughes, followed by a period of manic activity in which she wrote many of her best poems, a young woman isolated in the English countryside, caring for two children and having few material or mental health resources.

Specifically, what kindled my growing interest in Sylvia’s life—and, ultimately, in her published and unpublished works—was the posthumous publication of her extraordinary book of poems, Ariel (1965), and her autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar (1963). The unselfconscious revelations of her innermost thoughts and feelings contained in the journals and letters to her mother and her younger brother, Warren—and later to Hughes—fascinated me and fostered my determination to collect her reminiscences in poetry and prose.

“I could identify with the problems Plath faced in balancing marriage and motherhood with her professional ambitions—a tension that women from our generation knew all too well.”

My late husband, Robert Raymo, encouraged me in this process. He was a medieval scholar, an urbane academic dean and professor of English literature at New York University and an inveterate book collector. Together, we would traverse book auctions, book fairs and secondhand bookstores in New York and London, where we spent our summers. While his focus was primarily on Chaucer, I turned my attention to Plath, buying books and periodicals featuring her work as well as unpublished manuscripts. At the time, these items were available, inexpensive and in excellent condition.

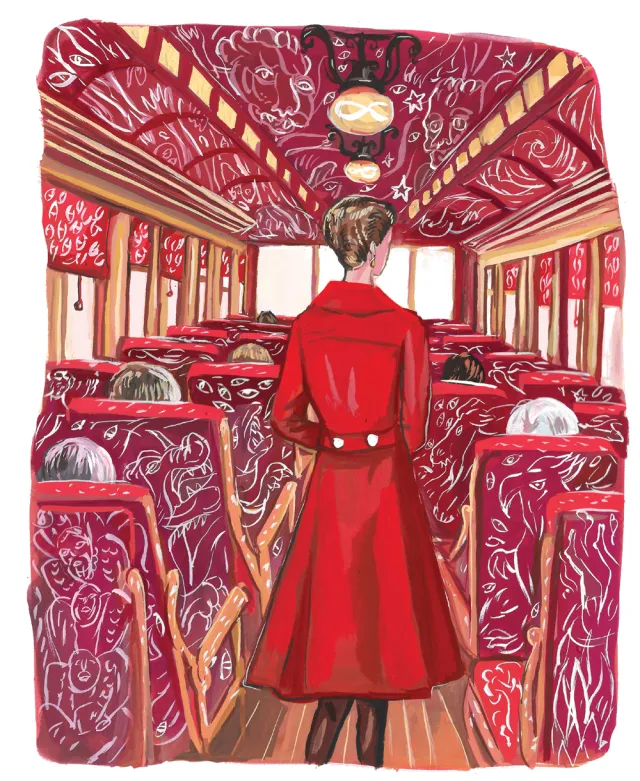

Sylvia Plath ’55 sets her story “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom” on a train, a popular way to travel in the 1950s. Each stop on Mary’s journey corresponds to one of Dante’s circles of Hell.

I became even more familiar with Plath’s poems in the winter of 2012, when I was asked to arrange a poetry evening as a member of the Grolier Club in New York City. Its members are bibliophiles, book collectors and rare-book librarians. Each January, we honor one poet with readings from his or her works. Through the generosity of Karen Kukil, then associate curator of special collections at Smith, I secured the help of her research assistant, Amanda (Mandy) Ferrara, who was a senior in the class of 2013 at the time. Mandy had been studying Plath’s poetry and shared with me her “favorites” from The Collected Poems anthology that Hughes had compiled (and that won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1982). Following some in-depth analysis, we assembled a syllabus of 27 poems that Grolier attendees would be asked to read aloud. As a prelude to the readings, Mandy gave a spirited talk about Plath and her poems. Her perspective as a young woman discovering poetry through the work of this mid-20th-century poet further inspired me to continue to build my collection, as did the enthusiasm of the Grolier audience that evening.

By 2016 my knowledge of and appreciation for Plath’s works had become even greater, and I decided that I wanted to host a Sylvia Plath exhibition. I submitted a proposal to the members’ exhibitions committee of the Grolier Club, and it was approved. The selection and installation processes were energizing, and from September 19 to November 4, 2017, we welcomed hundreds of Plath enthusiasts to This Is the Light of the Mind: Selections from the Sylvia Plath Collection of Judith G. Raymo in the club’s second-floor galleries. The exhibition was enhanced by framed photographs and books from Sylvia’s own library and a live video installation of the poet reading from her work. [A sidebar to this essay offers descriptions of some favorite works in my Plath collection.]

“The final typescript of ‘Mary Ventura’ is not only unique, but more importantly, it sparked the reexamination of a significant work by a writer known for her poetry rather than her prose.”

By the time of Plath’s death by suicide in February 1963—10 years after an earlier attempt—she had published hundreds of poems and some short stories in literary journals, magazines and anthologies, but only one book of poetry, The Colossus, and one novel, The Bell Jar. She left behind two young children, Frieda and Nicholas. Since she died without having made a will, her estranged husband, Ted Hughes (they had been married six years), gained control of much of her work, including her letters, journals, poems and stories. He became the main caregiver for their children and published several editions of her poems and a book of her short stories, Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams. Plath had lived life to the fullest, as she noted in her journals, which she kept from the age of 11. Unfortunately, that record is incomplete—Hughes destroyed her last journal, written within months of her suicide, and claimed that the previous one “had disappeared.” Many of her short stories remain unpublished, which brings me to the rediscovery and publication of “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom.”

Traversing Dante’s Circles

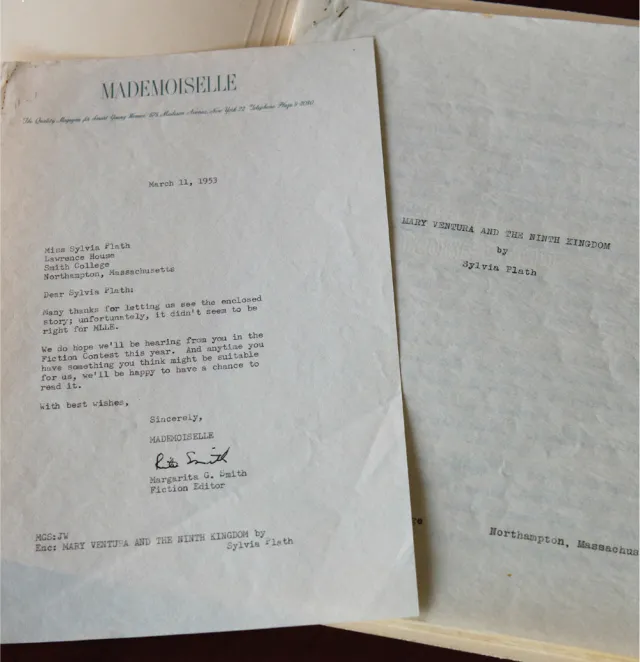

When Plath originally wrote “Mary Ventura” in 1952, she had been reading Dante for a rigorous medieval literature seminar that engaged with religious and allegorical texts. In November of that year, she wrote to her mother, “I will be lucky if I get a low B in the course … because the other seven girls in the class are all the most brilliant girls in the college.” “Oh, so very wrong!” Sybil Schless Steinberg ’54, one of her classmates, told me. “Mr. Patch [the professor] adored Sylvia: How could he not? He looked at her with benign affection and, in the end, Sylvia earned the only A in the course.” Indicative of her dependence on her mother, Aurelia Plath, Sylvia asked her to retype the story, make a few corrections and submit it on her behalf to Mademoiselle magazine. The magazine’s fiction editor rejected it in March 1953, commenting to Sylvia’s disappointment that it was “too fantastic and symbolic” for their readers.

In this story, named after one of Sylvia’s high school friends, Mary Ventura boards a train reluctantly, coaxed into it by her parents, who insist, despite her reluctance, “You just get on the train and don’t worry about another thing until you get to the end of the line.” At first, she resists entering the gate that is inscribed with the phrase (as in Dante’s Inferno) “Abandon all hope, you who enter.” Plath describes “a long row of red plush seats, the color of wine” as Mary slips “out of her red coat” and the train hurtles “through the black tunnel” into “a somber gray afternoon.” Mary senses a threatening atmosphere; she is fearful and cannot understand why the other passengers are so apathetic.

Matthew Collins, editor of Reading Dante with Images, has recently observed that “Mary Ventura” is an almost systematic reworking of Dante’s Inferno, ultimately “a fantasizing allegory of suicide, which a juxtaposed reading of Plath and Dante makes clear.” Plath sets her story on a train, our preferred means of transport in the 1950s. Mary’s train is scheduled to make nine stops, corresponding to Dante’s nine circles of Hell. Her guide, a self-assured older woman who has taken the trip before and can help Mary navigate the journey, advises her at key moments. The same is true of Virgil, Dante’s guide. At one point, the older woman says to Mary, I’m “talking in circles”—an attempt at humor, perhaps? In the Inferno, Dante traverses the River Acheron, entering the first circle of indifference. The second circle is inhabited by the lustful; the third by gluttons; the fourth contains the avaricious and dissolute as it traverses the River Styx; the fifth, the wrathful and the sullen; the sixth, the Epicureans (pleasure seekers); the seventh, the kingdom of negation and the frozen will. In Dante’s Hell, which includes the suicides, the eighth and ninth circles (sins of fraud and betrayal) are points of no return. Her companion warns Mary that she has only one assertion of the will remaining, so Mary, moved to action as she witnesses disturbances among the passengers, pulls the emergency cord just as the train reaches the platform of the seventh kingdom. Chased by the conductors, she runs up an unlit stairway until the darkness melts into a sunlit Paradise of “sweet air, earth, and fresh-cut grass.” Mary doesn’t die, she symbolically rises to Heaven.

As a sophomore at Smith, Sylvia Plath submitted her story “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom” to Mademoiselle magazine. Editors passed on it.

In his introduction to Robert Pinsky’s translation of Dante’s Inferno, the Renaissance scholar John Freccero observes that Dante viewed poetry as the “most important part of the poet’s biography,” sending him through Hell as a prelude to Enlightenment. Knowing that Sylvia attempted suicide eight months after writing this story, Collins asks if it is an “allegory of suicide” foreshadowing her unsuccessful attempt in 1953. Heather Clark, a biographer of Plath, concurs that the story’s “real subjects are depression, suicide, and rebirth.” I like to think that, affected by her reading of Dante’s masterpiece, Sylvia may have envisioned a more symbolic account of herself as an emerging poet.

When I was an undergraduate at Smith College, my life intersected briefly with Sylvia Plath’s. In collecting her work as an adult, I have revisited this earlier connection, piecing together parts of her life and literary career as I became familiar with her poetry and her prose. Often the most rewarding challenge for a collector is to move beyond foundational works, discovering unique and significant items in this quest. The final typescript of “Mary Ventura” is not only unique, but more importantly, it sparked the publication and reexamination of a significant work by a writer known for her poetry rather than her prose. For me, this has been an invigorating experience and presages my own search for what is new, meaningful and revelatory.

Judith G. Raymo has a doctorate in higher education from New York University, is professor emerita of education at Long Island University and, until her retirement, taught at Teachers College, Columbia University. She is the author and editor of books and articles on women in the academic workplace, including Shattering the Myths: Women in Academe (1999) and Unfinished Agendas: New and Continuing Gender Challenges in Higher Education (2008).

This story appears in the Spring 2021 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Favorite Plath Rarities and More

In her more than three decades of collecting, Judith Raymo ’53 has amassed a remarkable array of Sylvia Plath materials, including 125 rare books, some of which are first editions; 10 manuscripts; and 150 anthologies, adaptations and books of criticism.

Following are a few of Raymo’s favorite books from her collection.

About Sylvia by Enid Mark. Wallingford, Penn.: ELM Press, 1996. This hand-bound book is in a chemise of black Tiziano paper and includes lithographs by Enid Mark that utilize images of shattered glass. It contains 10 poems by poets who either knew Plath personally or who reflect on her life and work from the distance of time.

Ariel: The Restored Edition. A Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement. Foreword by Frieda Hughes. London: Faber & Faber, 2004. In this edition, Plath’s daughter, Frieda Hughes, has reinstated 40 poems to mirror Sylvia’s original schema, which had been altered by Plath’s husband, Ted Hughes, in the original 1965 edition.

Fiesta Melons. Exeter: Rougemont Press, 1971. Designed and printed by Eric Cleave, this limited hand-bound edition contains 10 poems and 14 lovely pen-and-ink drawings that demonstrate Plath’s artistic talent.

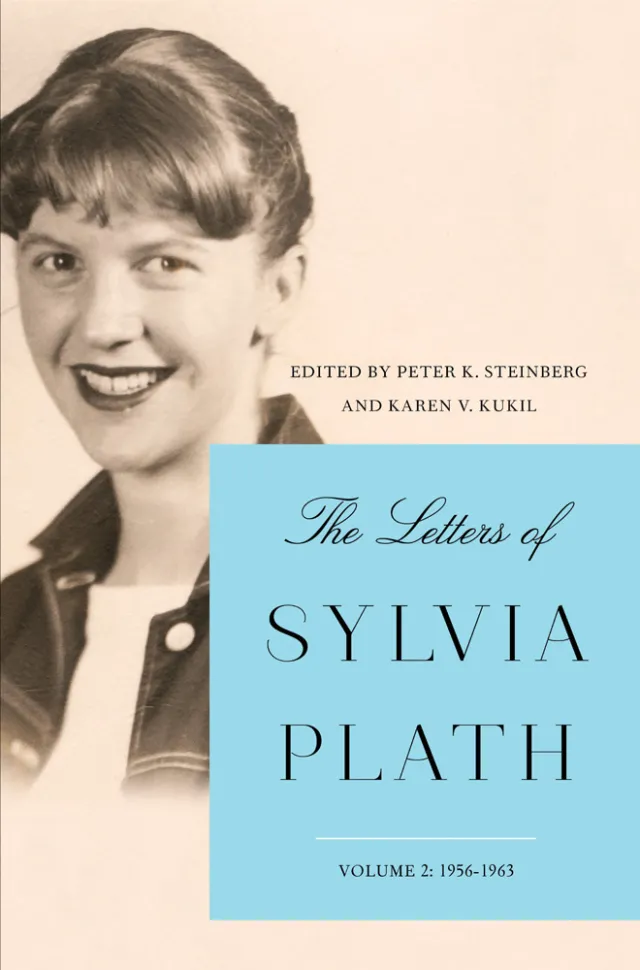

The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Volume 1: 1940–1956 and Volume 2: 1956–1963. Edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2017, 2018. These two monumental collections of Plath’s correspondence, presented unabridged and without revision, document her literary development and the genesis of her poems and stories, and provide details of her personal life.

Pursuit. London: Rainbow Press, 1973. Bound in leather, this book features an original etching and five black-and-white drawings by Leonard Baskin.

The Temple of Flora by Jim Dine. San Francisco: Arion Press, 1984. This artist’s book is a contemporary interpretation of Robert Thornton’s original book (1807), and has 28 black-and-white floral plates of flowers juxtaposed with tributes by modern poets that include Plath’s poem “Tulips.”

The Bell Jar by Victoria Lucas (Plath’s pen name). London: Heinemann, 1963. Plath’s only novel, written less than one month before her death, symbolizes the heroine’s entrapment by the conventions of 20th-century mores that she asserts are threatening her creativity and growth as an autonomous woman.

Judith Raymo ’53, pictured at her home in New York City, January 2021. Photographs by Peter Ross; illustrations by Jenny Kroik